Last updated August 5, 2022

Two absolutely delicious and ubiquitous dishes in Japan are ramen and gyōza.

The Japanese noodle soup ramen (ラーメン) is so well known it needs no translation. Ramen is ramen pretty much everywhere. There’s even a “steaming bowl” emoji that depicts a bowl of ramen: 🍜.

Gyōza (餃子)—Japanese pork & cabbage dumplings (usually pan-fried) that you dip in a mix of soy sauce, rice vinegar, sesame oil, and green onion—is less well-known but is likely familiar to anyone who has been to a Japanese restaurant (check for them the next time you go to one).

The slurpable noodles and salty broth plus the crunchy/tender pockets of pork-ginger-garlic goodness are an unbelievable combination. Even better than eating them separately, or eating gyōza as a side to your ramen, is to go ahead and put a sauce-dipped gyōza right into your noodle soup. Eat them together in one bite. YUM!

Warning: You will be hungry by the end of this post, if you aren’t already. I’ve been craving ramen and gyōza since I first came up with the theme of this post. Now that I’ve typed out the title, written a description, and added the photos, forget it. I have to go get some. NOW. RIGHT NOW!!!

ramen = ラーメン = 拉麺 = “pulled noodles”

gyōza = ギョウザ or ギョーザ = 餃子 = has the same characters used in the Chinese word for dumpling, jiaozi. The Japanese pronunciation approximates the Chinese pronunciation.

Gyōza variations include: pan-fried yaki-gyōza (焼き餃子); boiled sui-gyōza (水餃子); and deep-fried age-gyōza (揚げ餃子)

Did you notice that ramen and gyōza can be written with two different sets of characters? Japan actually uses three writing systems! One is the Chinese characters, or kanji (briefly introduced here). The second is hiragana, which refers to the Japanese phonetic writing system and is used for things like pronouns and the endings of adjectives and conjugated verbs. Katakana, the third type, is mainly used for writing foreign loan words but also, for example, to write sounds in manga. Like hiragana, it has 46 syllables and both cover the same syllables, just in different writing styles. Ramen and gyōza are both often written in katakana rather than kanji. You’ll also notice the use of the English-language, or Roman alphabet here and there, especially on signs and products. This alphabet is referred to as Roma-ji, or in a mix of katakana and kanji: ローマ字. It may seem confusing, but the systems all combine to work smoothly and coherently!

Ok, I’m back. Do I need to wait until you go get some? (…whistling…)

There are so many places where you can get ramen and gyōza, either as a meal or a snack. I just made some in my kitchen. I’ve always thought it would be great to make them from scratch (I even have recipes), but I’m lazy. Both of these foods are mass produced. Think of the packaged dried ramen noodles—such as Top Ramen or Maruchan, or the just-add-water Cup Noodles variety (you can soon see my post on the Cup of Noodles Museum), all of which are found in supermarkets pretty much everywhere. For gyōza, think of the frozen, identically-shaped, identically-sized dumplings sold in Asian specialty markets.

There are, naturally, many more options in Japan, including fresh refrigerated noodles or prepared gyōza at grocery stores. You can also readily find them—fast-food style—in train stations, department store restaurants, and shopping streets all over Japan. In some places, you simply walk into the shop, order from the self-service ticket machine, and wait a few minutes before being served. You can be done in time to catch the next train.

Ramen and gyōza are often associated with drinking. Gyōza is often available at izakaya 居酒屋, which are like Japanese-style pubs. But many ramen shops are open quite late. Ramen is a go-to snack after a night of drinking—for example, following after-work drinking parties, or nomikai 飲み会. Although some swear that eating ramen before staggering home helps ward off a hangover, others grab a canned energy drink at the nearest convenience store instead.

Futsukayoi 二日酔い (literally, “second day drunk,” is a great Japanese expression because it is so beautifully self-explanatory. The word is used just like “hangover.” To me, though, Futsukayoi so viscerally (and painfully) captures the fact that the effects of heavy drinking will take their toll on the next day.

Ramen and gyōza are also raised to the level of fine cuisine when the dish is made exquisitely by chefs who specialize in crafting one perfect product. The idea of honing a culinary skill—whether the broth for ramen, the hand-pulled noodles, or the gyōza’s balance of texture and flavor—to rarified perfection is part of Japanese culture (think of the fantastic movie Jiro Dreams of Sushi).

For ramen specifically, just look to the 1985 film Tampopo (by famous director Juzo Itami (伊丹 十三 Itami Jūzō)). This cult classic is a “ramen Western” instead of a “spaghetti Western” but is a comedy centered around food and food culture). Have you seen it? What’d you think?

You might also look to the “Ramen & Gyōza” volume of the long-running comic book series Oshinbo (美味しんぼ). Although translated as “The Gourmet,” 美味しんぼ is a wordplay that combines the words for delicious, oishii (美味しい) and kuishinbō (食いしん坊), or someone who loves to eat and eats too much.

Have you read it? What’d you think?

In one episode of this volume, a set of male twins own competing ramen shops only to find out they can only make the perfect bowl of ramen by combining their different skills in soup and noodle making. The competing brothers are Chinese men who are married to Japanese women.

This is clearly a nod to the Chinese origins of ramen. Gyōza are also of Chinese origin. Although the Chinese roots of these foods are not likely to surprise you, perhaps the relatively recent vintage of their popularity might. It wasn’t until after WWII that ramen and gyōza became a more regular part of Japanese diets. For more on this history, read George Solt’s The Untold Story of Ramen: How Political Crisis in Japan Spawned a Global Food Craze.

Since then, ramen and gyōza have become quite localized, with strong regional variations (for example, famous kinds like Hokkaido ramen (in the north) and Hakata ramen (in the south) almost seem like different dishes. And gyōza, too, has increasingly taken on more variation as annual gyōza festivals proliferate. Utsunomiya, the capital of Tochigi Prefecture, has made gyōza integral to the city’s brand and it even has a gyōza statue outside the Utsunomiya train station.

My family and I had some great gyōza at 餃子の福包 Gyōza no Fukuho in Shinjuku (a short walk from Shinjuku Gyoenmae Station (Marunouchi Line)) where you can order it fried (yaki-gyōza) or boiled (sui-gyōza) and with or without garlic. You can’t go wrong here. Everything we tried we delicious (it’s no coincidence that the name 福包 combines the characters for fortune and wrap) but I preferred the yakigyōza with garlic.

We tried to get some gyōza at 551 Horai (pronounced go-go-ichi Horai) but they had none. Not one. Foiled. At least it was for a good reason: they were supplying the police officers covering the G-20 summit held there in July 2019.

One of my favorite places to get ramen AND gyōza in recent years is at Kyoto Station, which has a whole floor (yes, a whole floor!!) devoted to ramen shops! Why is it so good? Because I can order a near-perfect combination of miso-based broth, thick noodles, buttered corn (you melt it right in the soup), and gyōza. The only thing they’re missing, in my opinion, is kimchi (Korean fermented cabbage), another side I like to put in the mix.

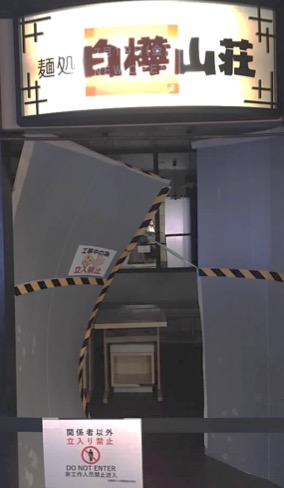

When I was with my family at Kyoto Station one afternoon, we were hungry and headed to the floor of ramen shops. I started imagining the bowl of ramen I would order, practically salivating as I climbed the long outdoor flights of stairs up to the 10th floor. When I made it up the stairs and down the hall to the storefront, I found this:

Nooooooo! Foiled again.

It was under construction and didn’t reopen until after I’d left Kyoto. Hopefully, it only underwent a cosmetic renovation. Next time I climb those stairs (you can take an elevator or escalators, if you prefer), I hope I can get the same great food.

That day, though, my family and I ended up at the very stinky Hakata ramen shop next door (the dirty-sock-like stench is notorious but it is possible to get used to it). It isn’t my favorite kind of ramen, which I hate to admit because I lived in Fukuoka for a year, but it filled our bellies.

I tried to end on a less tempting note, what with the smelly sock reference, but I am ALL in favor of you going to get your own fix of ramen and gyōza.

では またね!Thanks for reading!